|

| An activist in Cairo takes subversive action. |

In light of the amazing show of power by the people of Egypt, following on those in Tunisia, I am posting this sermon I gave at the First Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco.

Delivered March 2, 2008

Spiders can be divided into two simple categories: solitary spiders, which are the ones we are most familiar with – spinning small webs in the corners of our homes and gardens; and social spiders, who combine their efforts to spin large webs in order to catch clouds of flying insects which are shared among members of the web-weaving group.

One hot day last August, a worker in a state park was mowing a trail when he came upon a huge canopy of spider webs suspended from the branches of trees lining the path. The web was constructed of layers of sheets tens of feet across. It buzzed with the noise of millions of mosquitoes dying on its sticky strands. The web stretched over 200 meters. It was over one hundred times larger than the typical work of social spiders. Entomologists discovered that this collaborative project was the work of no fewer than twenty five species of spiders – the bulk of the weaving having been done by species normally considered to be solitary. Another anomaly was that this web was constructed within two months, while other collaborative webs of this size have typically been established over a period of years. It was as if hundreds of spiders woke up one day and decided to set aside their differences and their solitary tendencies and build this monumental project so as to feed their whole community – no matter what species they were.

What is our potential as humans to shift from working independently to meet our own needs, to transcending perceived differences in order to work for the greater good of the community?

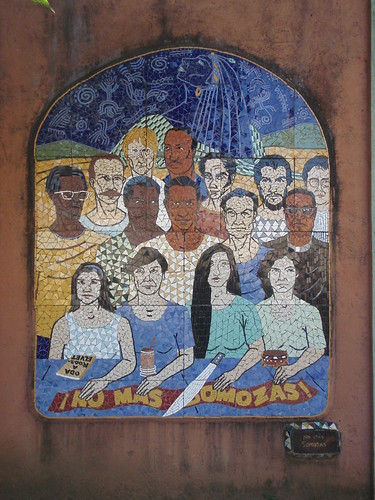

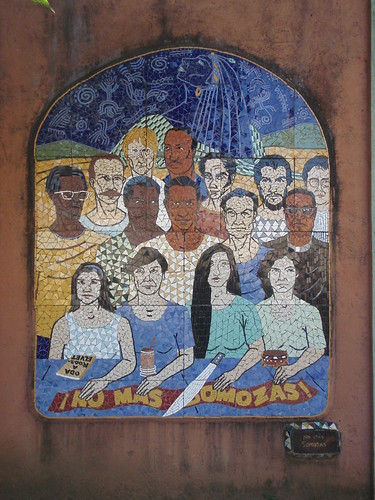

The ghosts of revolution haunt the streets of Leon, Nicaragua. There are murals and statues commemorating armed struggle and its heroes and martyrs throughout the city.

|

| The Cathedral in Leon |

On my second Retreat to Nicaragua with the Faithful Fools this past January, I was in Leon to get a taste of its history, to enrich the context of my experiences in that country's largest city, Managua, and the small farming village, San Diego, where we split the bulk of our two weeks in Nicaragua.

In a plaza across the street from Leon's old catholic cathedral, I was studying a huge mural when a woman approached and began explaining the painted symbols in Spanish simple enough that I could just barely understand. The story the mural told began with Mayan artifacts eroding in the sand – evidence of the first civilization known to have claimed the land we were standing on. Next were the helmet and long rifle of the Spanish conquistadors, who defeated the Mayans and claimed the country in 1524, and proceeded to establish the power of the Catholic Church. Footprints in the sand represented the next 300 years, arriving at a document signed by William Walker, a North American mercenary, backed by U.S. Business interests, who invaded Nicaragua in 1854 and declared himself president in 1856. Though he only ruled for a year, Walker's presence in the mural represented decades of U.S. Military invasion and political influence culminating in the election of Anastasio Somoza in 1936. Somoza and his family governed for over forty years; on the wall, a painted length of barbed wire half buried in the sand represented land the Somozas' had acquired for personal gain during their rule. Across the wire were the tools of the Sandinista Revolution, which overthrew the Somoza regime on July 19, 1979, and beyond that a scene showing the Sandinistas turning in their weapons to go into the countryside to teach the people to read - in what was a truly impressive literacy campaign. The final piece of the mural depicted children with a kite – my self-assigned tour guide said it represented the possibility of the future.

|

| Mozaic in Leon depicting revolutionaries |

It is was a beautiful mural, and though I have a hard time countenancing the violence, a beautiful story of a people reclaiming their resources – including their labor – for their own benefit after centuries of being exploited for the benefit of imperial powers. My guide, who introduced herself as Maria Elena, was clearly proud of what her people had done, and wanted to share that dream with me, so I could help spread it to my people. Which I suppose I am doing right now.

As Maria Elena and I sat down, I was feeling proud of being a part of this great story by being there in Nicaragua and having it told to me by someone who so obviously felt connected to it.

Soon my Spanish began to reveal its limits as she tried to explain something I wasn't fully comprehending. I was pretty sure she was describing how poor she was. She then pulled out a packet of postcards, including some with striking photos from the revolution, and tried to sell them to me. She also pulled out notes from other tourists recommending that I, or whoever she might be talking to, hire her as a tour guide. My pride began to subside, my head came out of the clouds that held dreams of revolution, and I felt myself returning to a capitalist reality I have, for years, longed to escape.

The layers of irony were too thick for me to fully comprehend as I purchased five of her revolutionary postcards for a dollar apiece, and made a point to tell her that where I come from I can get postcards for less.

And it seems this is where revolutions often end up. Movements start with the intent to redistribute wealth and power to those who had little of either and, time and time again, find themselves, once again, with people desperately lacking in what they need to survive.

It is important, of course, when looking at the Nicaraguan Revolution, to consider the role the US government played in its failure. As those who were paying attention in the early 1980's, or later in the Oliver North trial, know, the CIA trained and financed the Contras, a counterrevolutionary army, to fight the Sandinista government.

Sandinistas and some Nicaraguan scholars insist this war was responsible for the failure of the Revolution. It certainly was a major factor in the 1990 election which removed the Sandinistas from power.

I believe change is possible. So I am inclined not to reject revolution as a form doomed to failure, but to try to understand where it goes wrong, and how it can be made effective. I find hope in the story of the spiders, who changed their way of being and working together, to the benefit of the community. And as often happens with a good idea, this way of working spread. Within two months of the discovery of the giant web, six more were constructed in the region.

|

| Nicaraguan Faithful Fools on Retreat |

The first time I went on Retreat in Nicaragua, my host family asked me to rise early to eat breakfast with my host father, Fernando. The first morning, I rose in the dark, wiped the sleep from my eyes, and sat down at the table with Fernando while his wife Daisy prepared the meal. I really knew I was welcome, but with almost no Spanish at my disposal sitting with this friendly stranger felt awkward. I just smiled, trying to say “sorry I don't understand” and “thank you for having me here” with just the shape of my face. After it became clear I wasn't going to get anything he was trying to say, Fernando and I just sat and looked at one another, laughed a bit about our awkward situation, looked around the room a bit, and looked at each other again with friendly, hopeless smiles.

Daisy soon rescued us by coming out of the kitchen with bowls of rice with something on top. I say “something” because I wasn't sure what it was. It looked suspiciously like chicken in a tomato sauce, but it couldn't be chicken. I have been a vegetarian for over fifteen years, and those of us coming on the trip had talked several times about my diet, and how it would be no problem because of how much rice and beans our hosts eat. I was sure Carmen, who organized the trip, had told my family that I didn't eat meat.

I was sure until I took my first bite.

I finished the bowl of chicken and rice, mindful I was making a first impression, and not wanting it to be “ungrateful gringo.” Actually I didn't quite finish the bowl – I remembered Carmen saying that our hosts would take a clean plate as a signal that they hadn't provided enough food, and I wanted it to be clear that I didn't need any more chicken than they had already served me.

The only country in the western hemisphere with a lower per-capita income than Nicaragua is Haiti. We ask the families that host the Faithful Fools in the barrio in Managua and in San Diego, the farming community we stay in, to feed us as they do themselves. This has often meant, for me, eating less food than I am used to here at home.

It is pretty obvious that I'm not in need of a weight loss program. In fact, this year before I left for Nicaragua a few friends mentioned that they thought I might have been losing weight – I got on the plane hoping not to accelerate this possible trend.

My host mother in the barrio this year was Lijia. She lives with her two sons Roger and Erikson and her daughter Anna, as well as Anna's three boys, eight year-old Gustavo, Marlon, seven, and Minor, age 4. She supports her family by frying plantains in a huge pot over an open fire and selling them in the mercado, at sporting events, and on the street. She had also been the head of a soy kitchen that was in the community for a while a few years earlier. I had reason to expect I would eat well at Lijia's house.

I was not disappointed. My first meal consisted of steamed vegetables, fresh cheese, a few of Lijia's famous plantain chips, and gallo pinto, a traditional Nicaraguan red beans and rice dish. I ate it wholeheartedly, politely leaving a little bit of each item on the plate. It was good, and I was full – mission accomplished! Maybe I wasn't going to lose weight on this trip after all.

Then I noticed what the boys were eating. It didn't look to me like the feast I felt like I had been served. “Well”, I thought, “when I was their age I was a picky eater. Maybe they just don't like all these foods. And they're a lot smaller than me – maybe they wouldn't want to eat this much.” I wanted to feel okay about having taken what I did while they had what looked to me like so little.

I started doubting my justifications. “What if they eat so little because they're used to eating so little? Maybe they'd be bigger if they ate more.” I tried to excuse myself from responsibility for worrying about what the boys ate. My job was to be the guest: to gratefully receive what I was given and to show my appreciation by eating it enthusiastically. Maybe.

The next day, Lijia specially made me some soy patties – sort of like miniature hamburgers - to eat with rice and some more delicious plantain chips. She tried to feed them to the boys, but they wanted to stick to more familiar foods. It seemed the boys were picky – maybe I didn't have to worry about how little they ate, after all.

Emboldened by that thought, my desire to be a grateful guest, and the pressure of my friends' concerns about my possible weight loss, I ate everything on my plate. My Spanish, with the help of a dictionary, was good enough that I could just tell Lijia that I was full, and if she fed me a little more next time, that would be okay, too.

Then I noticed the pair of dogs that lived in the yard. They kept the house safe at night – burglary is taken for granted in Managua – and unlike many neighbors' dogs, they kept quiet during the day. Dog food is considered a luxury in Nicaragua; dogs are expected to forage in the garbage piles and eat scraps left from people's meals. I was really struck by the dog's ribs, visibly pressing against their short-haired pelts. Those dogs looked hungry, and the more I ate, the less they would eat.

I couldn't help but reflect on the messages that were floating through my head: The message from my friends, who worried that I was looking skinnier – not that I was going hungry, or that I was genuinely unhealthy, but just that I looked that way. The message I heard not just in my home, but in homes everywhere in the US: “clean your plate!” A message I can't directly trace, but which I think pervades our culture, which says the way we show our gratitude for our blessings is to consume them wholly and wholeheartedly.

Let's sit with that one for a moment.

I can certainly picture myself judging friends for being bashful about receiving gifts, or feeling awkward about how big their last raise was. “It's okay, you deserve it,” I might tell them.

And isn't this value present in the policies of our current government: that the US and its citizens are entitled to consume as much as we do because we can.

If that means trade policies that take advantage of economically weaker nations - “it's okay, we deserve it.”

If that means wars to secure oil resources - “it's okay, we deserve it.”

This sense of entitlement is familiar to us all. And I believe most of us are generally aware of its negative consequences, and would like to do something about them. We struggle to find a way to make a change which is meaningful.

But we are all a part of a system – social, economic, governmental, political – which supports us, some better, some worse, but which nonetheless supports us. If this system were to undergo drastic change all at once, to become subject to revolution, let's say, many of us would experience what might feel like a disaster. Lives would change, our access to resources would change. We don't know what else might change, and that is scary.

Let me say that again: For us, as a nation, a society, even just as a community, to make the kind of change that would feed the hungry dogs of the world and the hungry people, that would put a brake on wars over resources, that would preserve the environment – to make that kind of change is likely to involve changes that we don't feel we are ready for. And that is scary.

I think many, if not all of us, yearn for that change, or at least see it as needed, but we are afraid of what we stand to lose.

The 1979 revolution in Nicaragua happened, in part, because so many of the people in that country had been treated so horribly by the Samozas and other people in power. Most people could see that change for them was likely to be positive. The reality is that many people gained a lot, but many others lost. And much of what was gained was lost again.

Despite the broken promises made by so many revolutions – and we can all think of a few – I do still believe in change. I used to be a revolutionary in the traditional sense – wanting the systems to be overturned, for power to change hands, so the powerless would become the powerful. But we have seen time and again how the powerful, no matter what their roots are, tend to behave like the powerful.

As George Bernard Shaw said: “Revolutions have never lightened the burden of tyranny: they have only shifted it to another shoulder.”

So there must be another way. And I would say it is for us to revolve, to turn, inward and seek change. Not to overturn systems, and hope that the people they hold will be able to hold on, but to change ourselves, and to trust that the systems will change around us. As we reflect on the world, and on our own role in it, we are guided toward the changes we need to impact on us, in order to change the world.

And it takes courage, to face yourself.

And it takes courage, to change yourself.

And it takes courage, especially, to do the work of changing yourself when it is the world outside you want to change.

And fortunately, your courage has company. You are in a room full of people who have come to change themselves.

Look around. See them.

Smile at them.

Go ahead, wave at them.

These are your comrades, your companeros, in the revolution. And really, they are not just here, they are everywhere. They are out on the streets, in the parks, in our workplaces, hidden away in hospital rooms – you can find them if you look, and if you signal them. Smile at them, wave at them, say a kind word, and they will signal back, because to be successful, we must encourage each other.

We cannot do this work alone, we must be engaged in the work of the world. The world, in all its pain and injustice is our mirror, our guide to where we need to turn to make a change in ourselves.

I would like to close with another story, and an invitation.

This story was famously told by Carl Jung about Richard Wilhelm, translator of the Taoist I Ching:

“A rainmaker was asked to come make rain for a village that was experiencing a long and devastating drought. Though others had tried, no other holy man had been successful, and the village was on the edge of starvation. The first thing the rainmaker did was to ask to be given a hut, into which he secluded himself for four days and four nights until it began to snow.

Of course, Wilhelm wanted to know how he had done this. The rainmaker told him that when he came into the village he had noticed that the villagers were out of harmony with Heaven and Earth. He had spent the four days bringing himself into harmony, and once he did that, the snow came.”

I wanted to invite you all to join me in a Nicaraguan lunch this afternoon, but that would be dangerously close to communion, and Unitarians don't do communion, right? Oh, except for the Transylvanians. Well, a much more UU way to do it would be for us all to go have our own interpretation of a Nicaraguan meal. But if you want to join me after the silent auction at my favorite Nicaraguan restaurant, just ask me where it is, and I'll see you there.

One more message of hope as we navigate a sometimes bleak political landscape in this country: The spiders who spontaneously began to work together to weave the giant communal webs – they were all Texans!

May the fibers of connection we all weave together be strong!